In Bogotá, Colombia, amid long hugs, notebooks filled with notes, and that strange mixture of relief and nostalgia that one feels when something important comes to an end, the Clima-LoCa team closed its last workshop in Colombia.

Over three days—December 10, 11, and 12—science became everyday conversation, data became a roadmap for decision-making, and a six-year project felt, at times, like a family saying goodbye while still looking ahead.

Clima-LoCa was born out of the pursuit of a silent but decisive villain: cadmium. A heavy metal naturally present in many soils in the Andean region, cadmium can be absorbed by cacao plants under certain environmental and management conditions. Its accumulation not only puts the health of those who consume it in food at risk, but has also become a concrete trade barrier for producing countries, especially in light of European Union regulations, which today define which cacao enters international markets and which does not.

To address this challenge, Clima-LoCa was created from the outset with an interdisciplinary, international, and multi-stakeholder approach. The project opted to work simultaneously in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, three countries that share structural challenges in cocoa production and that, at the same time, could learn more from each other than by tackling the problem in isolation.

The interdisciplinary approach brought together experts in cocoa genetics, soils, climate, and socioeconomic analysis, recognizing that cadmium is not just an agronomic problem, but a complex phenomenon involving the interaction of environmental conditions, production decisions, and social realities.

“The complementarity between disciplines was key to understanding the problem holistically and seeking solutions” explained Mirjam Pulleman, project leader.

Mirjam Pulleman, project leader and senior scientist at the Alliance Bioversity International & CIAT.

This was complemented by work on multi-stakeholder platforms, in which producers, technicians, companies, governments, and research centers participated in the co-development of innovations adapted to different contexts. Because, although countries share common challenges, territories are different: different soils, different climates, different markets.

Under this approach, the project addressed its two major challenges: cadmium and climate change through concrete actions. The construction of maps and baselines on the presence of cadmium and the impacts of international regulation; and the identification and evaluation of agricultural practices and genetic materials with lower cadmium accumulation and greater climate adaptation. These evaluations were carried out both in controlled trials and in pilot projects directly on producers’ farms, including territories such as Boyacá and Putumayo in Colombia.

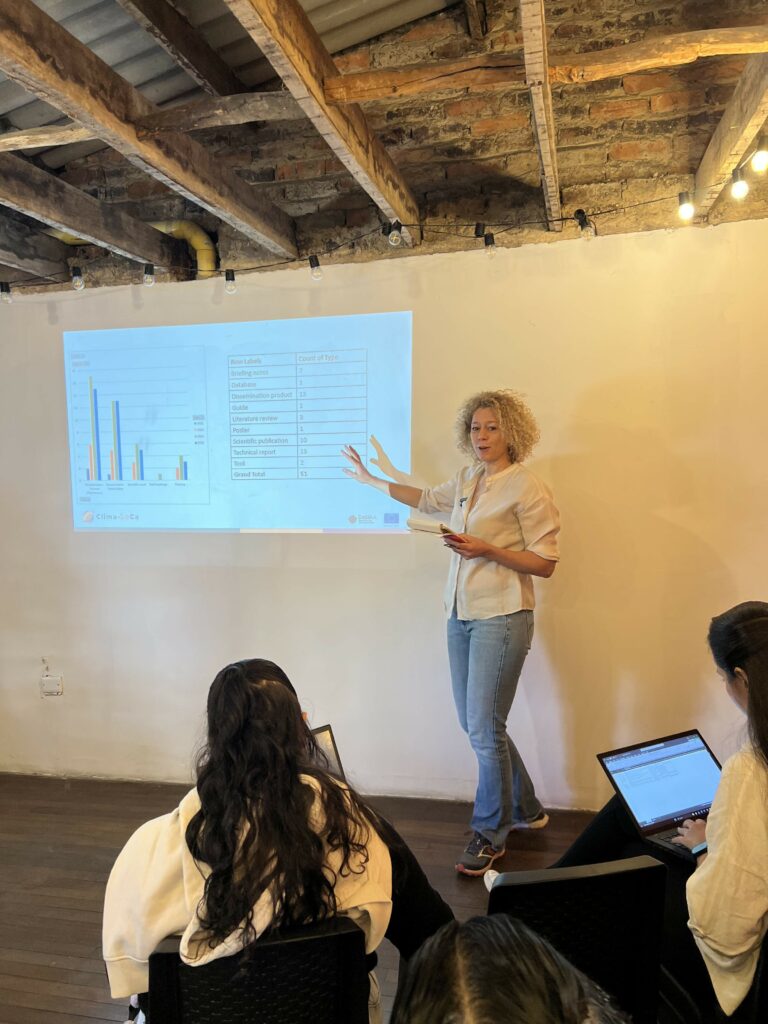

The first two days of the workshop were devoted to teamwork. After years of touring fields, farms, and crops in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, the project’s components—socioeconomics, cocoa genetics, soils and climate, and dissemination—sat down to put results on the table, compare methodologies, and validate findings built from different disciplines but with the same objective.

Mayessi da Silva, soil researcher at the Alliance Bioversity-CIAT and project coordination support, explained:

“Using different components and methodologies, we arrived at very similar results.” For her, this coincidence confirms that there are clear patterns in how climate change is affecting cocoa production systems and how these changes influence cadmium dynamics in soils.

Mayesse Da Silva, senior scientist at the Alliance Bioversity and CIAT, and coordinator of the Clima-LoCa project.

“We answered some questions, but we opened up a whole new ocean of questions to continue working on in the cocoa sector” she said, emphasizing that the end of the project does not mean the end of knowledge.

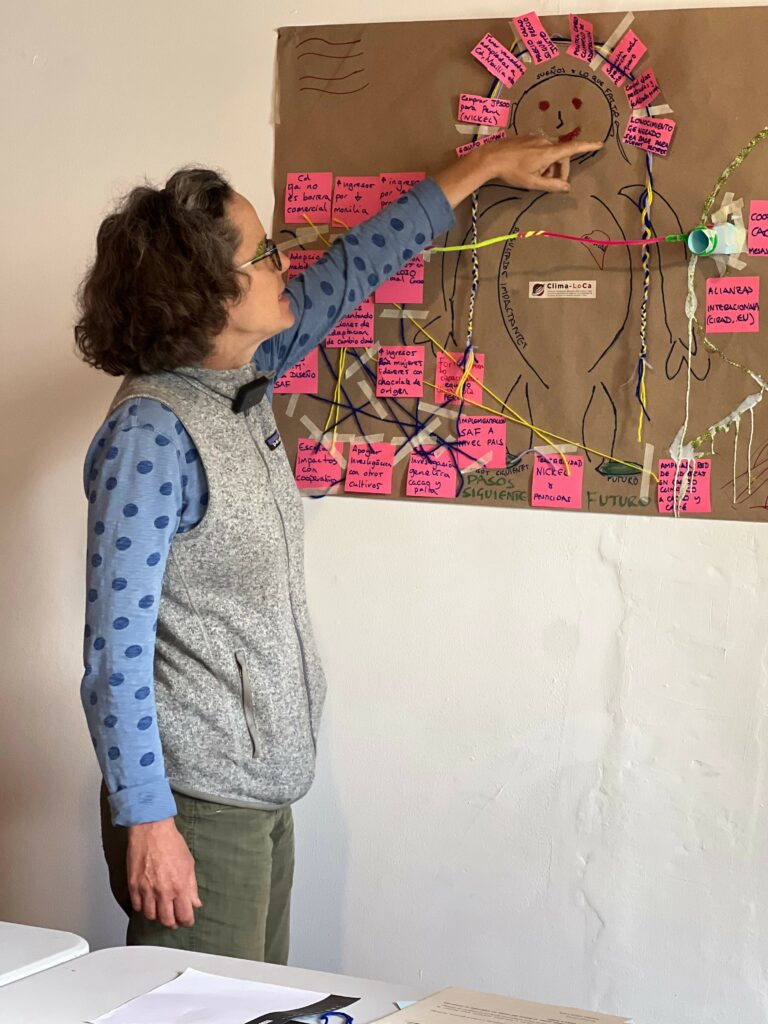

As part of this reflection, researcher Ana Bueno proposed a collective construction exercise in which the teams represented what had been built throughout the project in the body of a human being: in the head, ideas and pending issues; in the heart, networks and links; in the hands, impacts; in the torso, technical and scientific results; and in the feet, the paths that open up to the future. The exercise, as symbolic as it was revealing, condensed learnings, memories, and perspectives that had not always converged before.

Rachel Atkinson, focal point of the Clima-LoCa project in Peru.

Knowledge for decision-making

On the third day, December 12, the workshop was opened to other actors in the chain: technicians, representatives from the public and private sectors, international cooperation agencies, and producers. The focus was not only on scientific results, but also on their application: how to convert six years of research into real tools for decision-making.

From the outset, Clima-LoCa was clear that it could not speak only to academia.

“The idea was always to reach different beneficiaries” explained Mirjam Pulleman, project leader.

That is why, in addition to scientific publications, products were developed to influence public policy, production practices, and business decisions: briefing notes on regulation and safety, soil and climate databases, cadmium risk maps, technical guides, practical fact sheets, digital tools, and reports that are now circulating among producers, technicians, companies, and governments.

Joana Renckens, from Rikolto, recommended: “putting it into practice, sharing the results, and making it sexy”.

For her, the challenge is not only to produce valuable information and tools—maps, tools, mitigation measures—but also to bring that information down from the technical level and clearly convey it to decision-makers in the field. To this end, she proposes continuing to work as a team to achieve this goal in the three countries.

Eliseo Polanco Díaz, a master’s researcher at Agrosavia, emphasized scientific responsibility:

“Knowledge allows us to make good decisions” he said, insisting that the future of cocoa must be built on technical and scientific evidence, not on intuition, in order for the sector to grow and meet the required standards.

Partners and researchers during the closing day.

“This project danced with the ugliest girl” confessed Cristian Novoa, technical project manager at the National Association of Cocoa Exporters of Ecuador, referring to cadmium.

But he also left one thing clear: the information generated allows us to send a more accurate message to the world and prepare the sector to face not only current demands, but also those that will come in the future.

This link between science and the market was also evident in the domestic industry. Oscar Hincapié, agricultural development researcher at the National Chocolate Company, highlighted the role of Clima-LoCa as a strategic ally for decision-making in cocoa production projects.

“For us, Clima-LoCa has been a fundamental basis for making decisions with technical and scientific support” he said. He explained that the project’s work on climate change adaptation and soil risk mitigation has enabled the company to strengthen its support for the farmers who are part of its supply chain.

But the message went beyond cadmium. Hincapié pointed out that the project’s results pave the way for tackling new challenges in the sector, such as the presence of other heavy metals—nickel and lead—in different parts of the country, as well as socio-business challenges related to decent incomes, recognition of the role of women, and the empowerment of young people in the cocoa chain, as a condition for the future sustainability of the sector.

Panel of experts at the closing of the Clima-LoCa project.

Carmen Rosa Chávez Hurtado, a specialist from Peru’s Ministry of Agricultural Development and Irrigation, linked the lessons learned from the project to public policy decisions and proposed two tasks: certifying planting materials for farmers and incorporating these lessons into public, private, and cooperation investment projects that translate into sustainable income for cocoa producers.

Among the many voices, that of Rafael Higuera Ortiz, a producer from Yacopí, Cundinamarca, added to the meaning of the meeting. With seven years of experience in cultivation, working alongside his wife on just over two hectares, he concluded:

“This meeting has enriched us to take action in our own cultivation and minimize the negative effects of change”.

Juan Camilo Pineda, from the Geological Survey, emphasized that Clima-LoCa’s work responds to international regulations, yes, but also to an urgent need among small producers. That is why he highlighted the value of the project in generating new alliances between the public and private sectors and those who are directly involved in the territory.

At the close of the meeting, Mirjam Pulleman returned to an idea that ran throughout the workshop: the project ends, but the work continues. The data keeps coming in, the analyses are ongoing, and the results will continue to inform decisions.

“Clima-LoCa was not just about generating knowledge, it was about building trust between actors who did not always sit down to talk before” she said.

And perhaps that is why the atmosphere was not one of a final farewell. Rather than an end point, the workshop left a shared foundation: validated information, tools in use, and an active network between science, business, government, and producers.

Clima-LoCa team during the lockdown.

The final moment was led by Guillermo Zambrano (ESPOL Ecuador) and María Camila Giraldo, who played songs that have accompanied these years of collective work on a small guitar and maracas. A gesture to remind us that behind the data there are also people, territories, and a network that — like cocoa — does not grow on its own and no longer breaks.

Final day of the event.

Article written by: Camilo Beltrán Jacdedt.